3 SL2

In this section we discuss the finite-dimensional representation theory of the Lie algebra . We then use that to study the representation theory of , , , and , which are all closely related.

3.1 Weights

We fix the following ’standard’ basis of :

| and | ||||

These satisfy the following commutation relations, which are fundamental (check them!):

| and | ||||

We decompose representations of into their eigenspaces for the action of . The elements and will then move vectors between these eigenspaces, and this will let us analyze the representation theory of .

Since is simply connected, we have

Proposition 3.1.

Every finite-dimensional representation of is the derivative of a unique representation of .

Note that we have not proved this. However, we will use the result freely in what follows. It is possible to give purely algebraic proofs of all the results for which we use the previous proposition, but it is more complicated.

Proposition 3.2.

Let be a finite-dimensional complex-linear representation of . Then is diagonalizable with integer eigenvalues.

Proof.

By the previous proposition is the derivative of a representation of . We can identify as a subgroup of by the following map:

By Maschke’s Theorem for , on can be diagonalized. Taking the derivative, we see that can be diagonalized and hence so can .

In fact, the classification of irreducible representations of shows that has eigenvalues in and so has eigenvalues in . ∎

Remark 3.3.

The proof of the proposition is a instance of Weyl’s unitary trick. We turned the action of , which infinitesimally generates a non-compact one-parameter subgroup of , into the action of the compact group infinitesimally generated by . The action of this compact subgroup can be diagonalized.

The proposition does not hold for an arbitrary representation of the one-dimensional Lie algebra generated by . Namely, the map cannot be diagonalized. It is implicitly the interaction of with the other generators and which makes the proposition work.

Let be a finite-dimensional complex-linear representation of . By Proposition 3.2 we get a decomposition

| (3.1) |

where each is the eigenspace for with eigenvalue :

Definition 3.4.

-

1.

Each occurring in equation (3.1) is called a weight (more precisely, an -weight) for the representation .

-

2.

Each is called a weight space for .

-

3.

The nonzero vectors in are called weight vectors for .

Example 3.5.

The set of weights of the zero representation is empty, while the trivial representation has a single weight, .

Example 3.6.

Let be the standard representation. Write for the standard basis. Then and . Thus the set of weights of is .

Example 3.7.

We consider the adjoint representation of on itself. By the commutation relations, we see directly that has eigenvalues (), (), and (), so the set of weights is

The non-zero weights and are called the roots of and their weight spaces are the root spaces and . The weight vectors are called root vectors.

Thus we have the root space decomposition

Example 3.8.

We consider where is the standard representation. Then

and similarly

so that the weights are . Note that this is a multiset — a set with repeated elements — and we say that the weight 0 has ‘multiplicity two’ (in general, the multiplicity of a weight is the dimension of the weight space).

Example 3.9.

Take . A set of basis vectors is

We calculate

Thus the weights are (writing ):

We will soon see an explanation for this pattern.

3.1.1 Highest weights

The following is our first version of the fundamental weight calculation.

Lemma 3.10.

Let be a complex-linear representation of . Let be a weight of and let . Then

and

Thus we have three maps:

Proof.

We have, for ,

So as required.

The claim about the action of is proved similarly. ∎

Definition 3.11.

A vector is a highest weight vector if it is a weight vector and if

In this case we call the weight of a highest weight.

Lemma 3.12.

Any finite-dimensional complex linear representation of has a highest weight vector.

Proof.

Indeed, let be the numerically greatest weight of (there must be one, as is finite-dimensional) and let be a weight vector of weight . Then has weight by the fundamental weight calculation, so must be zero as was maximal. ∎

Example 3.13.

Let . Then the highest weight vectors are and .

These are easily checked to be highest weight vectors — the first is killed by since , the second becomes

It is left to you to check that there are no further highest weight vectors.

3.2 Classification of representations of sl2,C.

The key point here is that a highest weight vector must have non-negative integer weight , and it then generates an irreducible representation of dimension whose isomorphism class is determined by and which has a very natural basis of weight vectors.

Let be a complex-linear representation of .

Lemma 3.14.

Suppose that has a highest weight vector of weight . Then the subspace spanned by the vectors

is an -invariant subspace of .

Moreover, , the dimension of is , are a basis for , with .

Proof.

Let be the span of the . Since the are weight vectors, their span is -invariant. It is clearly also -invariant. So we only need to check the invariance under the -action. I claim that for all ,

| (3.2) |

The proof is by induction. The case is:

If the formula holds for , then

| (induction hypothesis) | ||||

as required.

If is not a nonnegative integer, then for all . So

whence for all . As these are weight vectors with distinct weights, they are linearly independent and so span an infinite dimensional subspace.

If for some , then

and so . Repeating gives that , a contradiction.

Now,

and so is either zero or a highest weight vector of weight . We have already seen that the second possibility cannot happen, so .

Thus is spanned by the (nonzero) weight vectors with distinct weights, which are therefore linearly independent and so a basis for . ∎

Remark 3.15.

If we didn’t assume that was finite-dimensional, then the first part of the previous lemma would still be true.

Corollary 3.16.

In the situation of the previous lemma, is irreducible.

Proof.

Suppose that is a nonzero subrepresentation. Then it has a highest weight vector, which must be (proportional to) for some . But then

if and so , meaning that . But then for all , so as required. ∎

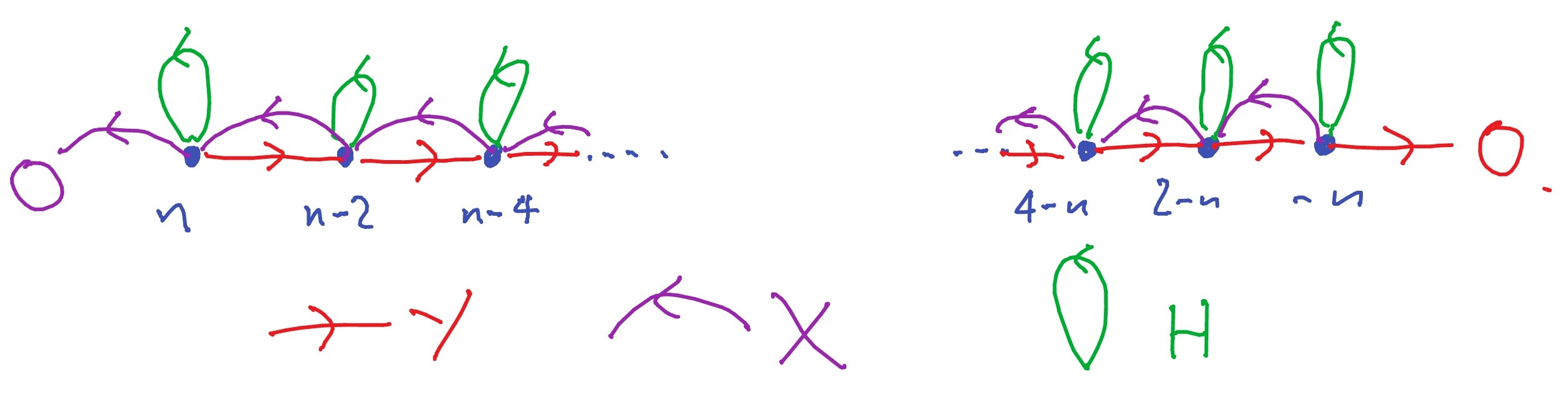

The weights of are illustrated in Figure 3.2.

Theorem 3.17.

Suppose is an irreducible finite-dimensional complex-linear representation of . Then:

-

1.

There is a unique (up to scalar) highest weight vector, with highest weight .

-

2.

The weights of are .

-

3.

All weight spaces are one-dimensional (we say that is ‘multiplicity free’).

-

4.

The dimension of is .

For every , there is a unique irreducible complex-linear representation of (up to isomorphism) with highest weight .

Proof.

Let be an irreducible finite-dimensional complex-linear representation of . Let be a highest weight vector. By Lemma 3.14 its weight is a nonnegative integer , and by Corollary 3.16 the vectors span an irreducible subrepresentation of of dimension , which must therefore be the whole of . The claims all follow immediately.

Moreover, the actions of , and on this basis are given by explicit matrices depending only on , so the isomorphism class of is determined by .

It remains only to show that a representation with highest weight exists for all . Consider . The vector is a highest weight vector of weight , so we are done. In fact, in this case is proportional to , so the irreducible representation generated by is in fact the whole of . ∎

In fact, if is the irreducible representation with highest weight , highest weight vector , then the matrices of , , and with respect to the basis

are respectively

| and | ||||

Theorem 3.18.

Every finite-dimensional irreducible complex-linear representation of or is isomorphic to , the symmetric power of the standard representation.

Proof.

We already proved this for . If is a representation of , then its derivative will be isomorphic to . Since is connected, this implies that . ∎

3.3 Decomposing representations

Theorem 3.19.

Let be any finite-dimensional complex-linear representation of . Then is completely reducible, that is, splits into a direct sum of irreducible representations.

Proof.

We will prove this later (Theorem 3.30) using the compact Lie group . ∎

It is easy to decompose a representation of into irreducibles by looking at the weights. Firstly, look at the maximal weight of . Then there must be a weight vector of weight , which is necessarily a highest weight vector, and so must contain a copy of — namely, the subspace . By complete reducibility we have

The weights of are then obtained by removing the weights of from the weights of , and we repeat the process.

In particular, this shows that a finite-dimensional representation of is determined, up to isomorphism, by its multiset of weights.

Proposition 3.20.

If , are representations of then:

-

•

weights of weights of weights of .

-

•

weights of sums of unordered -tuples of weights of .

-

•

weights of sums of unordered ‘distinct’ -tuples of weights of .

Proof.

Omitted: try it yourself! For a similar result, see section 4.5 below. ∎

Example 3.21.

We should illustrate what is meant by ‘distinct’: it is ‘distinct’ as elements of the multiset. Suppose that the weights of are . Then to obtain the weights of we add together unordered, distinct, pairs of these in every possible way, getting:

Example 3.22.

Let be the standard representation of with weight basis , . Consider . Let , and be weight vectors in corresponding to the weights , and . Then the weights of are

-

•

, multiplicity one, weight vector: .

-

•

, multiplicity two, weight space: .

-

•

, multiplicity three, weight space: .

-

•

, multiplicity two, weight space: .

-

•

, multiplicity one, weight vector: .

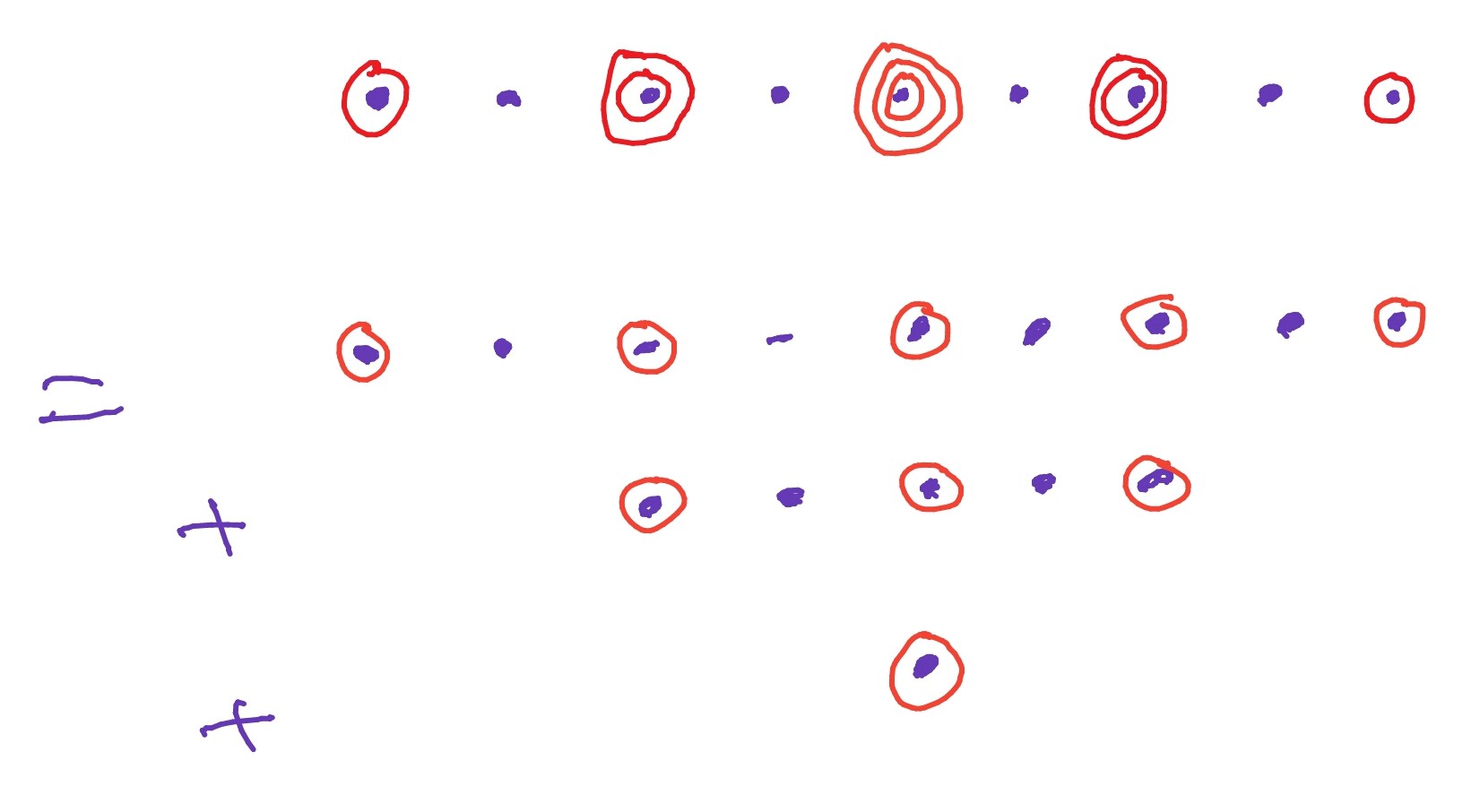

The weights of are and so the weights of are

This is the same as the set of weights of

and so this is the required decomposition into irreducibles.

We can go further, and decompose into irreducible *sub*representations. This means finding irreducible subrepresentations of such that is their direct sum.

The copy of in has highest weight vector . We can find a basis by repeatedly hitting this with (writing for ‘equal up to a nonzero scalar’):

These vectors are a basis for the copy of in .

Next, we find the copy of in . We start by looking for a highest weight vector of weight 2:

does the trick. Hitting this with gives , and doing so again gives (up to scalar). These vectors are a basis for the copy of in .

Finally, we find the trivial representation in . We need only find a weight vector of weight 0 which is killed by , and

does the job: this vector spans a copy of the trivial representation.

3.4 Real forms and complete decomposability

We use our understanding of the representation theory of into an understanding of the representation theory of and , and prove complete reducibility.

Definition 3.23.

A real form of a complex Lie algebra is a real Lie algebra such that every element of can be written uniquely as for .

Remark 3.24.

In lectures, we didn’t give this definition, just doing the special case of .

For dimension reasons, necessary and sufficient conditions are that and .

Example 3.25.

The Lie algebra is a real form of .

Example 3.26.

The Lie algebra is a real form of . Indeed, and if then

so .

Explicitly, we may write as with

and

in .

Example 3.27.

Recall that

Let

Since the defining equation can be checked separately on the real and imaginary parts of ,

and so is a real form of .

Proposition 3.28.

Let be a real form of .

There is a one-to-one correspondence between representations of and complex-linear representations of under which irreducible representations correspond to irreducible representations.

Proof.

Given a -linear representation of , it is a representation of by restriction. Conversely, if is a representation of , then it extends to a unique -linear representation of given by the formula (forced by -linearity)

It is easy to see that this preserves the Lie bracket. The proposition follows (the final statement is left as an exercise). ∎

As a corollary we immediately obtain

Theorem 3.29.

The representation theories of and are ‘the same’ as the complex-linear representation theory of . All finite-dimensional irreducible representations of , , , or are of the form .

Proof.

The claims about Lie algebras follow from the above discussion. Every (finite-dimensional) irreducible representation of is of the form , and these clearly exponentiate to representations of , despite this not being a simply connected group! Similarly for (which is simply connected). Since and are connected, every representation of them is determined by its derivative, so we have a complete list of the irreducible representations. ∎

Theorem 3.30.

Every finite-dimensional complex-linear representation of is completely reducible.

Proof.

Let be a finite-dimensional complex-linear representation of and let be a subrepresentation. Then is an -subrepresentation. As is simply-connected, and exponentiate to representations of . Since is compact, by Maschke’s theorem there is a complementary -subrepresentation with

Then is a -subrepresentation, and so a -linear -subrepresentation, so that

as representations of . Complete reducibility follows. ∎

The argument in this theorem is called Weyl’s unitary trick. For a similar application of this idea, see the proof of Proposition 3.2.

3.5 SO(3) (non-examinable)

We skipped this section, due to the strike, so the material is non-examinable.

3.5.1 Classification of irreducible representations

We have already (see the first problem set this term) seen that and are isomorphic. We therefore have:

Theorem 3.31.

There is an irreducible two-dimensional representation of (coming from ) such that the irreducible complex representations of are exactly

for .

We want to know which of these representations exponentiate to an irreducible representation of . For this, we revisit the connection with .

Let be the bilinear form on defined by

Lemma 3.32.

The form is a positive definite bilinear form preserved by the adjoint action of .

Proof.

The bilinearity is clear. To see that it is positive definite, if then

Direct calculation shows is the sum of the squares of the entries of , which is strictly positive for nonzero .

We have, for ,

which shows that this inner product is -invariant. ∎

Corollary 3.33.

There is an isomorphism

Proof.

Choosing an orthonormal basis for with respect to identifies the set of linear maps preserving the inner product with . We therefore have a homomorphism

whose kernel is . The derivative of this homomorphism is injective, otherwise there would be a one-parameter subgroup in the kernel of the group homomorphism, and since the Lie algebras have the same dimension we get an isomorphism of Lie algebras. The group homomorphism is therefore surjective, since exponentials of elements of generate the group . ∎

Remark 3.34.

Let be the elements of given by

respectively. Up to scalar, these are an orthonormal basis for . Since the derivative of the above homomorphism is the adjoint map, computed with respect to this basis, we see that the induced isomorphism takes:

It will be useful to know where this isomorphism takes the elements of . For example, as , we see that it goes to . Or, for the lowering operator , we have

and similarly .

Corollary 3.35.

For each , there is a unique irreducible representation of of dimension .

The derivative of this representation is isomorphic to the representation of .

This gives the complete list of irreducible representations of up to isomorphism.

Proof.

We simply have to work out which representations of exponentiate to a representation of . Since we have

and each exponentiates to a unique representation of — which we also call — this is equivalent to asking for which the centre of acts trivially on . But we see that acts as , so the answer is: for even only.

Thus exponentiates to a representation of if, and only if, is even, and we obtain the result. ∎

We can consider the weights of these representations. Under the isomorphism

the element maps to . Since the -weights of are , we must divide these by to find the weights of acting on :

Example 3.36.

Consider the standard three-dimensional representation of on . The weights of are simply its eigenvalues as a matrix, which are . We see that this representation is isomorphic to .

3.5.2 Harmonic functions

We can use our understanding of the representation theory of to shed light on the classical theory of spherical harmonics.

We let be the subspace of consisting of homogeneous polynomials of degree . This has an action of given by

where is a vector in . We therefore get a representation of .

Lemma 3.37.

The elements , and of act on according to the following formulae:

Proof.

Exercise. In fact, prove that the action of is given by

by considering

at (where we rewrite as ). ∎

It will be useful in what follows to recall

Lemma 3.38.

(Euler’s formula) If is a homogeneous polynomial of degree , then

The representation is not irreducible. Let be the polynomial

Note that is clearly invariant under the action of .

Lemma 3.39.

The map defined by

is an injective homomorphism of -representations.

Proof.

We have, for ,

as required. ∎

Next, we consider the Laplace operator:

This is map from .

Lemma 3.40.

The map is a map of representations.

Proof.

We must show that, for ,

We have

and so

We sum over , for fixed and :

since is orthogonal. We therefore obtain

and therefore

∎

An element is harmonic if . Since , harmonic polynomials must exist. We write for the space of harmonic polynomials.

Lemma 3.41.

On , we have

Proof.

Left as an exercise. ∎

It follows that preserves each irreducible subrepresentation of (since do). Furthermore, by Schur’s lemma it must act on each irreducible subrepresentation as a scalar. We determine that scalar.

Lemma 3.42.

Suppose that is an irreducible subrepresentation with highest weight . Then

Proof.

Since is a -homomorphism and is irreducible, by Schur’s lemma it acts as a scalar on . It therefore suffices to compute the action on a highest weight vector . So

It follows that and, as

we have .

Applying the previous lemma gives the result. ∎

Theorem 3.43.

For every ,

The space is the irreducible highest weight representation of of dimension , and the space , as an -representation, is the direct sum of representations of weights , each occurring with multiplicity one.

Proof.

We use induction on . The case is clear (we just have the trivial representation). Suppose true for with .

By the previous lemma, the space is the sum of all the copies inside of the irreducible representation with highest weight . Since does not contain this irreducible representation, by the inductive hypothesis, we have

Since, as already discussed, its dimension is a positive multiple of . However, its dimension is at most

It follows that is irreducible, and that we have

The statement about the decomposition into irreducibles follows. ∎

The proof of this theorem shows that

so that every polynomial has a unique decomposition as a sum of harmonic polynomials multiplied by powers of .

We can go further and give nice bases for the by taking weight vectors for . First, we have

Lemma 3.44.

The function is a highest weight vector of weight .

Proof.

Exercise! ∎

We then obtain a weight basis by repeatedly applying the lowering operator

The functions thus obtained are known as ’spherical harmonics’ (at least, up to normalization), and give a particularly nice basis for the space of functions on the sphere . The decomposition of a function into spherical harmonics is analogous to the Fourier decomposition of a function on the unit circle.

Example 3.45.

If , then , and the weight vectors are

If , a basis of made up of weight vectors is