4 SL3

We now discuss the finite-dimensional complex-linear representation theory of . This then tells us everything about the holomorphic representations of and, via the machinery of real forms, tells us about representations of and .

Much of what we say, particularly at first, will generalise in a fairly obvious way to .

In this section, all representations of will be assumed to be complex-linear.

4.1 The Lie algebra sl3,C

We study the Lie algebra

of traceless matrices. It has dimension . We first need to find the analog of the standard basis of

First, notation: we write for the matrix with a ’1’ in row and column , and ’0’ elsewhere. Then if and only if .

The analogue of will be the entire subalgebra of diagonal matrices.

Definition 4.1.

The (standard) Cartan subalgebra of is , given by

Note that is an abelian subalgebra, because diagonal matrices commute with each other.

We pick as a basis of the elements

| and | ||||

and also define .

Next we consider the adjoint action of on , seeking eigenvectors and eigenvalues. The key calculation is:

Exercise 4.2.

Check this!

Thus is a basis of simultaneous eigenvectors in for the adjoint action of .

4.2 Weights

Suppose that is a finite-dimensional complex-linear representation of . Suppose that is a simultaneous eigenvector for all , . Then, for each , there is an such that . Since is complex-linear, is a complex-linear map . In other words, is an element of the dual space . This motivates the following definition:

Definition 4.3.

Suppose that is a representation of . Then a weight vector in is such that there is (the weight) with:

for all .

The weight space of is

On we have some ‘obvious’ functionals given by

These span , subject to the relation44 4 More precisely, is isomorphic to the quotient of the three dimensional vector space with basis by the subspace spanned by .

We compute the weights of some particular representations.

Example 4.4.

If is the standard representation of (for which for all ), then the standard basis vectors are all weight vectors:

from which we see that for all . See table 1.

| Weight | |||

| Weight vector |

Example 4.5.

If is the dual of the standard representation then it has a basis defined by

One can show that is a weight vector of weight , so the weights are . See problem 37.

Example 4.6.

Let be the symmetric square of the standard representation. The rules for calculating the weights of are the same as for — so, for the symmetric square, we add all unordered pairs of weights of . For details see section 4.5 The weights of are and so the weights of are

Note that, if we wanted, we could also write etc.

Example 4.7.

Let with the adjoint representation defined by . As already observed, we have

for and , while for . Thus the weights of the adjoint representation are () and . The weight space for is , which has dimension two with basis and ; we say that the weight has multiplicity two in . We obtain table 2.

Definition 4.8.

A root of is a nonzero weight of the adjoint representation. A root vector is a weight vector of a root, and a root space is the weight space of a root.

In other words, a root with root vector is a nonzero element such that

We write

for the set of roots of . Out of these, we call the positive roots and the negative roots. We write ; these are the simple roots. Note that is the sum of the two simple roots. We will sometimes write for the root .

Finally, we have the root space or Cartan decomposition

where the are the root spaces, which are all one-dimensional.

Exercise 4.9.

Work through all the above theory in the case of . What are the roots and root spaces? What is the relation between the weights (as linear functionals on ) and between the weights defined in section 3?

4.3 Visualising weights

Shortly we will prove that, if is a finite dimensional representation of , then its weights are integer linear combinations of the . In other words, they lie in the weight lattice

Exercise 4.10.

Show that if and only if . Must the be integers?

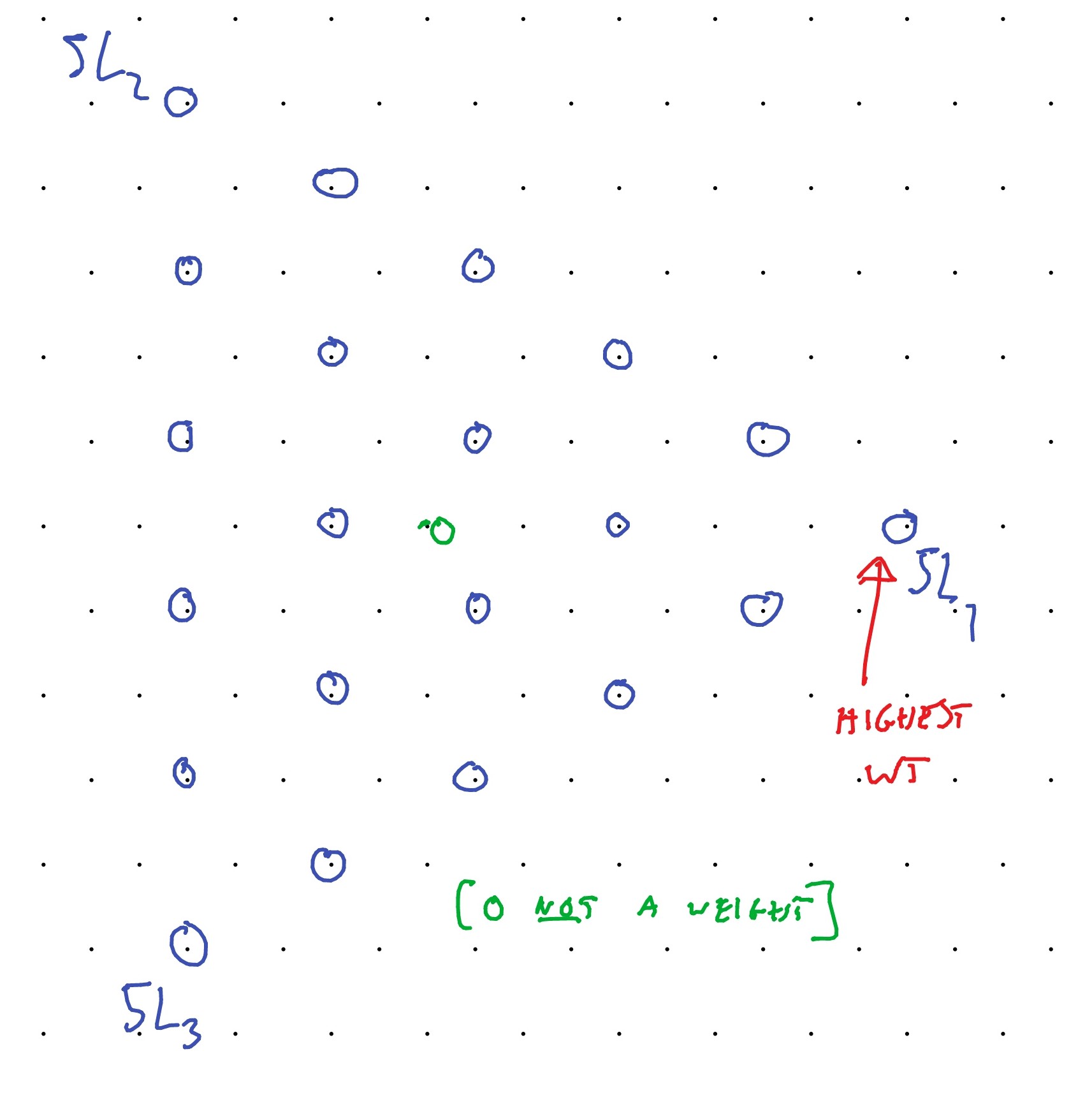

We want to visualise this in a way that treats symmetrically. Noticing that they sum to zero, we regard them them as the position vectors of the vertices an equilateral triangle with unit side length, centred on the origin. The weight lattice is then the set of vertices of equilateral triangles tiling the plane. For any representation , its weight diagram is then obtained by circling the weights that occur in that representation.

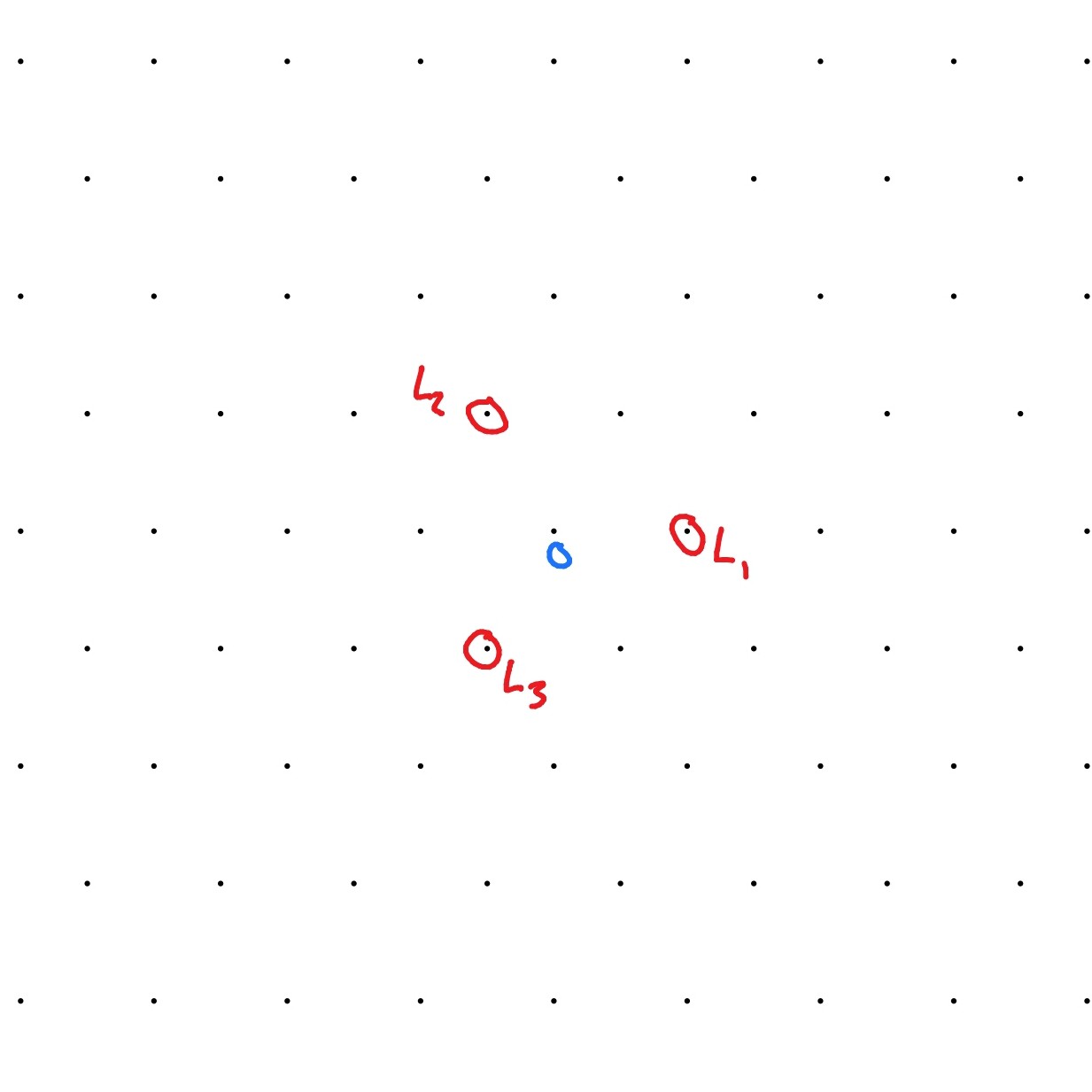

Example 4.11.

We draw the weight diagram for the standard representation, in Figure 5.

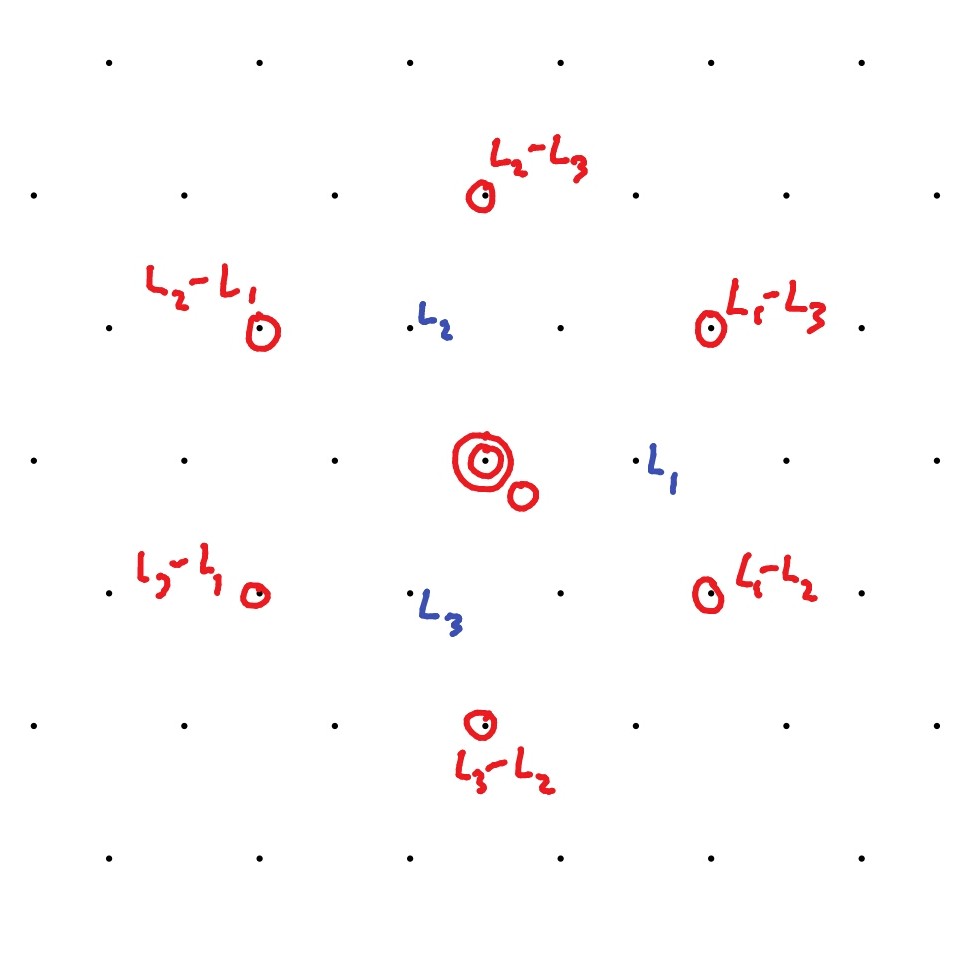

Example 4.12.

We draw the weight diagram for the adjoint representation in Figure 6. Note that in this case the dimension of the weight space for the weight is two. We say the weight has multiplicity two, and indicate this on the weight diagram by circling the weight twice. If the multiplicity was much higher, we would need another method (like writing the multiplicity next to the circle as a number).

4.4 Representations and weights

Firstly, we recall from above that any finite-dimensional representation of is completely reducible. This is Theorem 3.30 above, that we proved using the ’unitary trick’.

Theorem 4.13.

Let be a finite-dimensional representation of . Then:

-

•

There is a basis of consisting of weight vectors.

-

•

Every weight of is in the weight lattice .

We may combine these two into the single equality

Proof.

Consider the embedding embedding a matrix into the ‘top left’ of a matrix:

This is a Lie algebra homomorphism, and is a representation of . We know from the theory that

is diagonalizable with integer eigenvalues. If is a weight vector with weight , then it is an eigenvector for with eigenvalue . Thus is an integer.

Now, there is another embedding putting a matrix in the ‘bottom right’ corner. The same argument then shows that is diagonalisable with integer eigenvalues, which shows that is an integer for every weight.

Thus every weight is in the weight lattice. Moreover, and are diagonalizable, and they commute with each other since and commute and is a Lie algebra homomorphism. A theorem from linear algebra states that commuting, diagonalizable matrices are simultaneously diagonalizable. It follows that there is a basis of consisting of simultaneous eigenvectors for and . Since and span , this is a basis of weight vectors. ∎

Remark 4.14.

There is a third homomorphism

We have .

Note that, for , and , so and will play the role of raising and lowering operators.

Remark 4.15.

We could also prove Theorem 4.13 by exponentiating to a representation of and considering the action of the subgroup of diagonal matrices with entries in , which is compact (isomorphic to ). Compare the proof of the statement that the weights of representations of are integers.

4.5 Tensor constructions

We did not go through these proofs in lectures in detail, so I only expect you to know how to apply these results in situations similar to those in lectures or in the problems class.

We record how the various linear algebra constructions we know about interact with the theory of weights. If is a representation of then we consider its weights as a multiset

where and each is written in this list — the multiplicity of — times.

Suppose that is another representation of with multiset of weights

Theorem 4.16.

Suppose that are as above. Then:

-

1.

The weights of are .

-

2.

The weights of are

-

3.

The weights of are

-

4.

The weights of are

Proof.

Let be a basis of weight vectors of such that has weight , and let be similar for with weights .

-

1.

The dual basis is a basis of weight vectors in with having weight .

-

2.

If has weight and has weight , then for all ,

So is a basis of with the given weights.

-

3.

Similarly to the previous part,

is a basis of with the given weights.

-

4.

Similar.

∎

Remark 4.17.

Similar considerations apply to representations of (or ).

4.6 Highest weights

We now develop the theory of highest weights, analogous to that for . We first carry out the fundamental weight calculation (the analogue of Lemma 3.10).

Lemma 4.18.

(Fundamental Weight Calculation). Let be a representation of and let be a weight vector with weight . Let be a root and let be a root vector. Then

Thus we obtain a map

Proof.

Let . Then

Example 4.19.

We work this out for the adjoint representation. Recall that, for , we have the root with root vector . The above calculation shows that, if and are roots, then . Here are some examples:

-

•

If , , then is not a root so . Thus (which could also be checked directly).

-

•

If then we get

-

•

If , , then and we get

In fact, you can check that .

Exercise 4.20.

Let be a finite-dimensional irreducible representation of . Then the weights occurring in all differ by integral linear combinations of the roots of , that is, by integral linear combinations of .

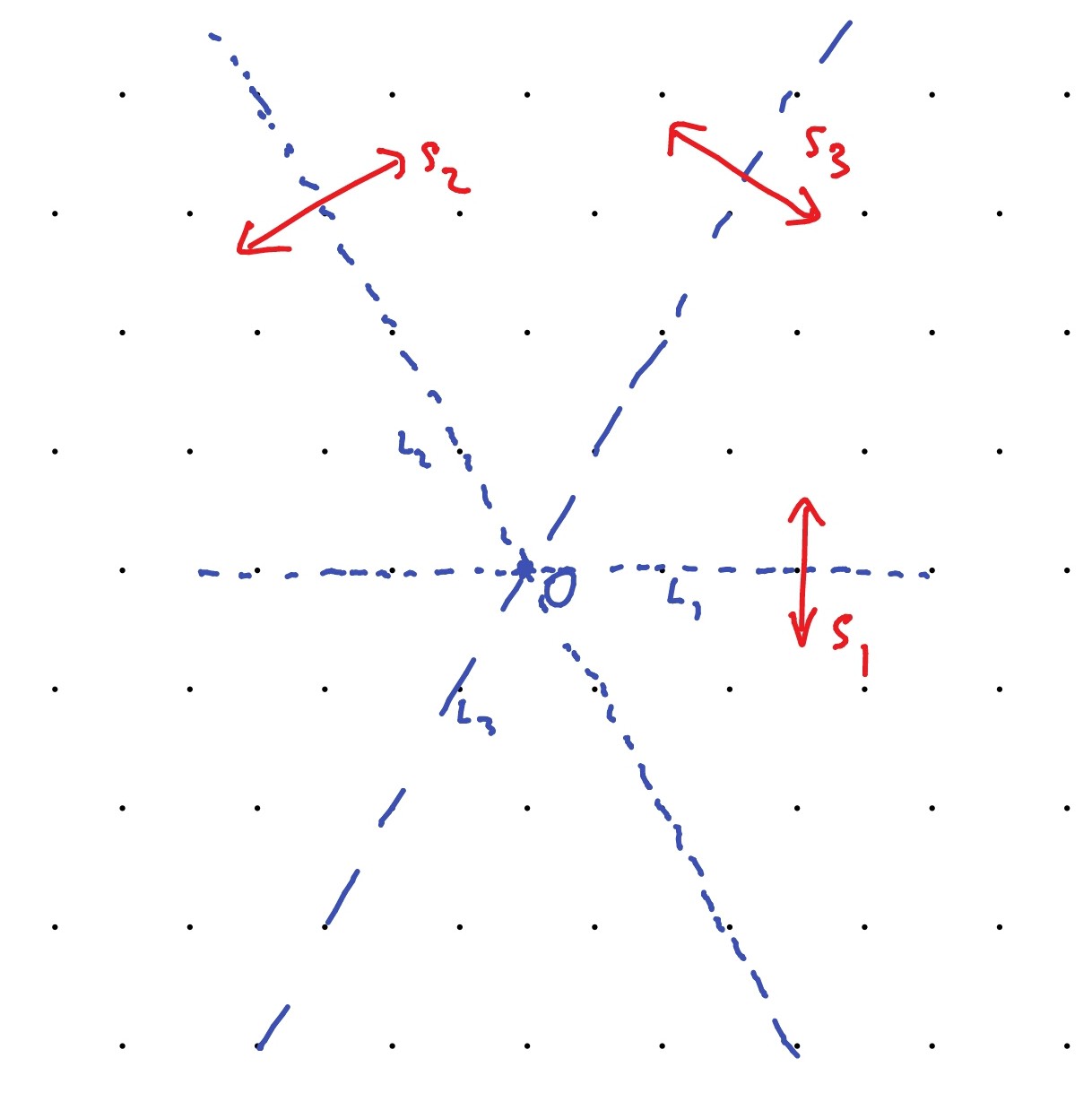

With regard to the weight diagram, we observe that the ’positive’ root vectors , , move in the ’northeast’ direction while the ’negative’ root vectors move in the ’southwest’ direction (roughly speaking). See Figure 7.

Definition 4.21.

Let be a representation of . A highest weight vector in is a vector such that:

-

1.

is a weight vector; and

-

2.

.

The weight of is then a highest weight for .

Remark 4.22.

Since , it follows that a highest weight vector is also killed by . So it is killed by all the positive root vectors.

Example 4.23.

-

1.

The standard representation has highest weight with highest weight vector .

-

2.

The dual has highest weight with highest weight vector .

-

3.

The adjoint representation has highest weight with highest weight vector .

-

4.

The symmetric square has highest weight with highest weight vector .

Lemma 4.24.

Let be a finite-dimensional representation of . Then has a highest weight vector.

Proof.

For a weight , define . Of all the finitely many weights of , choose a weight such that is maximal.

Let be a weight vector with this weight. Then , if nonzero, has weight

and

This is not a weight of by maximality of . Thus . Similarly , if nonzero, has weight

and , so . ∎

4.7 Weyl symmetry — not examinable

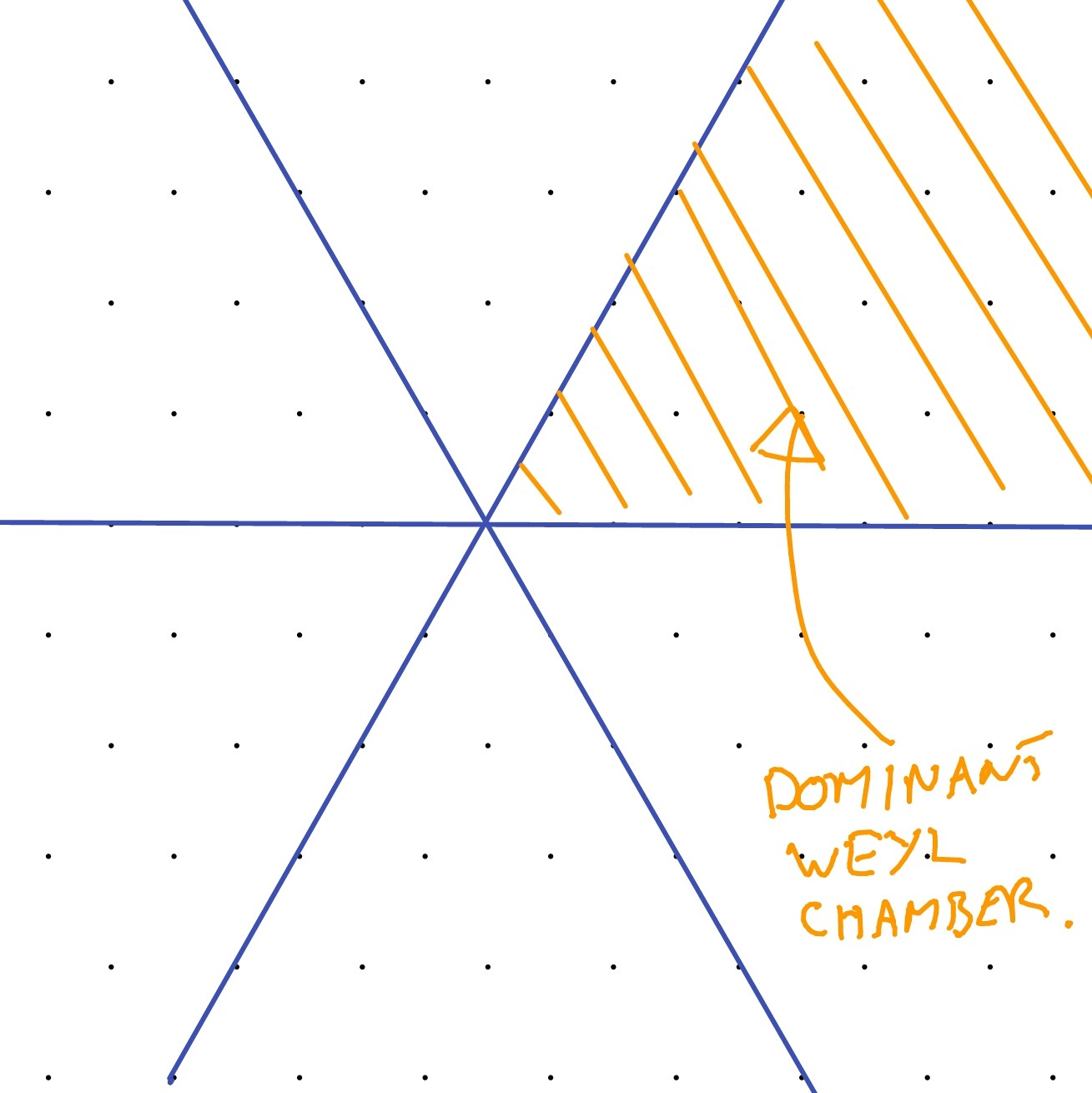

Let , , and be, respectively, reflections in the lines through , , and . Then any two of these (say and ) generate the Weyl group , which is the group of symmetries of the triangle with vertices . So we have . Note that acts on the plane in a way that preserves the weight lattice. See Figure 8.

Theorem 4.25.

Let be a finite-dimensional representation of . Then the weights of are symmetric with respect to the action of the Weyl group.

Proof.

We will prove they are symmetric with respect to by using the inclusion

that puts a matrix in the top left corner of a matrix. We consider the restriction of to .

Note that if is a weight vector with weight , then

Thus is an -weight vector with weight . Note that , so an -weight vector in is an -highest weight vector if it is killed by . Note also that .

The kernel of on is preserved by (check it!) and so has a basis made up of -weight vectors . These are then a maximal set of linearly independent highest weight vectors for and in particular, if is the -representation generated by then, as an -representation,

Fix ; it suffices to show that has a basis of -weight vectors whose weights are preserved by . Let have weight . It follows from the -theory that and — remembering that — that has a basis

By the FWC (Lemma 4.18) we see that these are weight vectors with weights

which are symmetrical under (this reflection swaps and ), as required. This argument is illustrated in Figure 9

Invariance with respect to the other reflections is proved similarly using the other inclusions of in . ∎

Corollary 4.26.

Every highest weight is of the form for integers. The region

is called the dominant Weyl chamber and weights inside it (including the boundary) are dominant weights.

Proof.

Indeed, in the course of the proof of Theorem 4.25 we showed that if was a highest weight, then . A similar argument shows that . ∎

Exercise 4.27.

We can give another proof of Weyl symmetry using the Lie group . Let be a representation of . As is simply-connected exponentiates to a representation, , of . Let

Show that, for every weight , is an isomorphism

Give another proof of Theorem 4.25.

4.8 Irreducible representations of sl3,C.

We are now in a position to state the main theorem of -theory.

Theorem 4.28.

For every pair of nonnegative integers, there is a unique (up to isomorphism) irreducible finite-dimensional representation of with a highest weight vector of weight .

Note that the highest weights occurring in the theorem are exactly the dominant elements of the weight lattice.

Since every irreducible finite-dimensional representation does have a highest weight, necessarily dominant, every irreducible representation is isomorphic to for some integers .

Example 4.29.

We have already seen some examples:

-

1.

The standard representation is irreducible with highest weight , therefore

-

2.

The dual to the standard representation is irreducible with highest weight , and so

-

3.

The adjoint representation is irreducible with highest weight , and so

-

4.

The symmetric square has highest weight with highest weight vector .

Exercise 4.30.

(Problem 44). Show that, if is a finite-dimensional representation of with a unique highest weight vector (up to scalar), then is necessarily irreducible.

Deduce that the three representations listed above are indeed irreducible.

For a more general example, we have:

Exercise 4.31.

(Problem 46; non-examinable). Show that the representation has a unique highest weight vector with weight . Deduce that

Convince yourself that the weights in this case are as shown in Figure 11 (which illustrates the case ).

4.9 Proof of theorem 4.28 — nonexaminable

Lemma 4.32.

Let be a finite-dimensional representation of . Let be a highest weight vector of weight , and let

Then

-

1.

is a subrepresentation of

-

2.

i.e. is the unique weight vector in of weight , up to scaling.

-

3.

is irreducible.

Proof.

-

1.

Let

Then

Firstly, it is clear that and take to , and so preserve . Since

we see that also preserves .

Secondly, every is a weight vector (by the fundamental weight calculation) and so an eigenvector for all , . Thus preserves each (and hence also ).

Finally, we show that preserves . A similar proof then applies for , and then preserves by the same argument as for . We prove the statement for by induction on .

For , . Since is a highest weight vector, and so .

Suppose that the claim is true for . Consider with . We must show that . Suppose first that . Then, as , we have

by the induction hypothesis and the fact that is preserved by as required. The proof in the case is similar, using that .

-

2.

Note that if the weight of , with and as in the lemma, then a calculation using the fundamental weight calculation, as in the proof of lemma [[ref:lem-hwv-exists]], shows that

and so if . Since these vectors span , is the unique (up to scalar) weight vector in of weight .

-

3.

Suppose that is reducible. By complete reducibility (Theorem [[ref:thm-complete-reducible-sl]]) we have

for nonzero proper subrepresentations of . We must have for unique . The unicity implies that and are both weight vectors of weight ; by part 2, either or . So without loss of generality . But then all as is a subrepresentation, so contradicting that is a proper subrepresentation.

∎

Remark 4.33.

It follows that as in Lemma 4.32 is actually the subrepresentation generated by , that is, the span of all vectors obtained by applying arbitrary elements of some number of times. The content of the lemma is then that it suffices to apply only and .

We are now ready to prove Theorem 4.28:

Proof.

First we show the existence. Let . Consider

This has a highest weight vector of weight . Let be the representation generated by . Then is irreducible by 4.32 part 3, and has a highest weight vector of weight . Thus we can take .

Next we show the uniqueness. Suppose that are two irreducible representations with highest weight vectors and , respectively, of weight . Let be the representation generated by . Then is irreducible by 4.32 part 3. The projection sending to restricts to a homomorphism which sends to . This is therefore a nonzero homomorphism between irreducible representations, and so must be an isomorphism. Thus . Similarly , and so as required. ∎

In fact, it is possible to give an explicit description of the irreducible representations; see problem 47.

Theorem 4.34.

Let . Let

be the map

Then is a surjective -homomorphism, and its kernel is the irreducible representation with highest weight .