$$ \usepackage{derivative} \newcommand{\odif}[1]{\mathrm{d}#1} \newcommand{\odv}[2]{\frac{ \mathrm{d}#1}{\mathrm{d}#2}} \newcommand{\pdv}[2]{\frac{ \partial#1}{\partial#2}} \newcommand{\th}{\theta} \newcommand{\p}{\partial} \newcommand{\var}[1]{\text{Var}\left(#1\right)} \newcommand{\sd}[1]{\sigma\left(#1\right)} \newcommand{\cov}[1]{\text{Cov}\left(#1\right)} \newcommand{\cexpec}[2]{\mathbb{E}\left[#1 \vert#2 \right]} $$

1 Probability

1.1 Introduction to Probability

1.1.1 What is probability?

Probability is how we quantify uncertainty; it is the extent to which an event is likely to occur. We use it to study events whose outcomes we do not (yet) know, whether this is because they have not happened yet, or because we have not yet observed them.

We quantify this uncertainty by assigning each event a number between 0 and 1. The higher the probability of an event, the more likely it is to occur.

Historically, the early theory of probability was developed in the context of gambling. In the seventeenth century, Blaise Pascal, Pierre de Fermat, and the Chevalier de Méré were interested in questions like “If I roll a six-sided die four times, how likely am I to get at least one six?” and “if I roll a pair of dice twenty-four times, how likely am I to get at least one pair of sixes?” Many of the examples we’ll see in this course still use situations like rolling dice, drawing cards, or sticking your hand into a bag filled with differently-coloured tokens.

Nowadays, probability theory helps us to understand how the world around us works, such as in the study of genetics and quantum mechanics; to model complex systems, such as population growth and financial markets, and to analyse data, via the theory of statistics.

We’ll see a bit of statistical theory at the end of this chapter, but will mostly stay on the probabilistic side of that line.

1.1.2 Events

Because events are subsets of the sample space, we can treat them as sets.

1.1.2.1 Set operations

There are three basic operations we can use to combine and manipulate sets.

1.1.2.2 Working with events

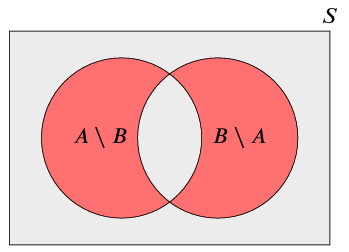

When we want to consider all the outcomes in an event \(A\) which are not in \(B\), we write \(A \cap B^c = A \setminus B\).

We say that two events are disjoint (or incompatible, or mutually exclusive) if they cannot occur at the same time; in other words, if \(A\) and \(B\) are disjoint, then \(A \cap B\) contains no outcomes.

We write \(A \cap B = \emptyset\), and we call \(\emptyset\) the empty set.

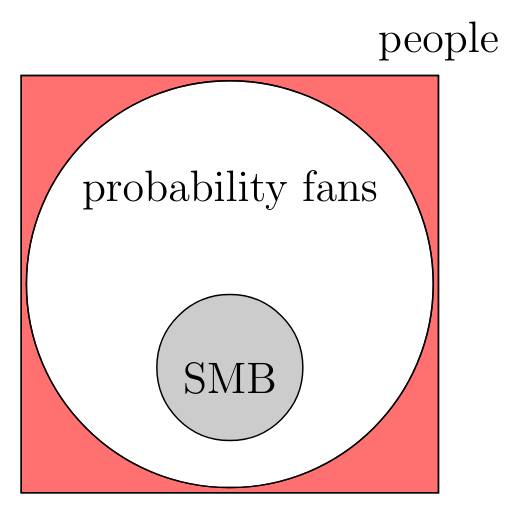

If every outcome in an event \(A\) is also in an event \(B\), we say that \(A\) is a subset of \(B\), and we write \(A \subseteq B\).

The following set of basic rules will be helpful when working with events.

Commutativity: \[ A\cup B = B\cup A, \quad A\cap B= B\cap A\] Associativity: \[(A\cup B)\cup C = A\cup( B\cup C), \quad ( A\cap B)\cap C= A\cap(B\cap C)\] Distributivity: \[(A\cap B)\cup C = (A\cup C)\cap( B\cup C), \quad (A\cup B)\cap C=(A\cap C)\cup( B\cap C)\] De Morgan’s laws: \[(A\cup B)^c = {A}^c\cap{B}^c, \quad (A\cap B)^c ={A}^c\cup{B}^c \]

1.1.3 Axioms of Probability

Once we have decided what our experiment (and hence our sample space) should be, we assign a probability to each event \(A \subseteq S\). This probability is a number, which we write \(\mathbb{P}(A)\).

Remember that \(A\) is an event, which is a set, and that \(\mathbb{P}(A)\) is a probability, which is a number. It makes sense to take the union of sets, or to add numbers together - but not the other way around!

We need a system of rules (the axioms) for how the probabilities are assigned, to make sure everything stays consistent. There are lots of such systems, but we will use Kolmogorov’s axioms, from 1933. There’s no particular reason to choose one system over another, but these are a popular choice.

We can use set operations to see some immediate consequences of the axioms:

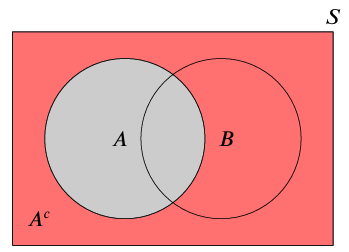

Since \(A\) and \(A^c\) are disjoint, we have \(\mathbb{P}(A^c) = \mathbb{P}(S) - \mathbb{P}(A) = 1 - \mathbb{P}(A)\).

Impossible events have probability zero: \(\mathbb{P}(\emptyset) = 0\).

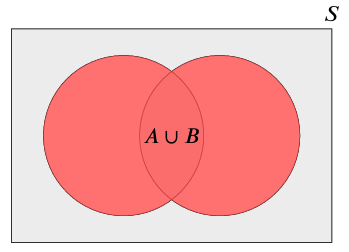

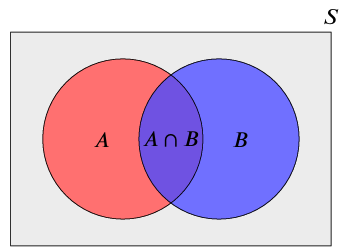

For (not necessarily disjoint) events \(A\) and \(B\), we have \(\mathbb{P}(A \cup B) = \mathbb{P}(A) + \mathbb{P}(B) - \mathbb{P}(A \cap B)\).

If \(A \subseteq B\), then \(\mathbb{P}(A) \leq \mathbb{P}(B)\).

Suggested exercises: Q1 – Q10.

1.2 Counting principles

In this section, we look at some different ways to count the number of outcomes in an event, when the events are more complex than, say, a roll of a die.

1.2.1 The multiplication principle

If our experiment can be broken down into \(r\) smaller experiments, in which

the first experiment has \(m_1\) equally likely outcomes

the second experiment has \(m_2\) equally likely outcomes

\(\cdots\)

the \(r\)th experiment has \(m_r\) equally likely outcomes,

then there are \[\begin{aligned} m_1 \times m_2 \times \dots \times m_r = \prod_{j=1}^r m_j \end{aligned}\] possible, equally likely, outcomes for the whole experiment.

In general, sampling \(r\) times with replacement from \(m\) options gives \(m^r\) different possiblities.

1.2.2 Permutations

When we select \(r\) items from a group of size \(n\), in order and without replacement, we call the result a permutation of size \(r\) from \(n\).

A special case is when we want to arrange the whole list. Then, there are \[\begin{aligned} r \times (r-1) \times \dots \times 1 = \frac{r!}{0!} = r! \end{aligned}\] different permutations.

1.2.3 Combinations

When we select \(r\) items from a group of size \(n\), without replacement, but not in any particular order, then we have a combination of size \(r\) from \(n\).

Two useful ways of thinking about combinations:

You might notice that \({n \choose r} = {n \choose n-r}\). This is because we can also look at the combination of items we don’t pick. It’s much easier (psychologically, at least) to list the different ways to leave 3 cards in the deck than it is to list the different ways to draw 49 cards!

There is a relationship between combinations and permutations: \[\begin{aligned} \text{the number of combinations} = \frac{1}{r!} \times \text{ the number of permutations}. \end{aligned}\] This is because each combination counted when the order doesn’t matter comes up \(r!\) different times when the order does matter.

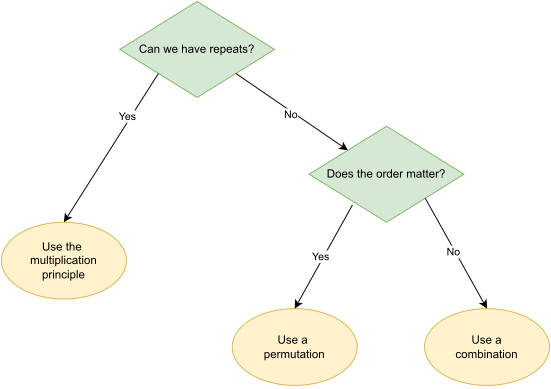

Remember: If we’re allowed repeated values, the only tool we need is the multiplication principle.

If there can be no repeats (sampling without replacement), then we use permutations if the objects are all distinct, and combinations if they are not. Usually if we’re dealt a hand of cards, or draw a bunch of things out of a bag, then they’re indistinguishable. But if we’re rolling several dice, or assigning objects to people, then we can (hopefully) tell the dice or people apart.

You might find the flowchart in Figure 1.3 helpful.

1.2.4 Multinomial coefficients

When we want to separate a group of size \(n\) into \(k \geq 2\) groups of possibly different sizes, we use multinomial coefficients.

To see how this works, think about choosing the groups in order. There are \(\binom{n}{n_1}\) ways to choose the first group; then, there are \(\binom{n-n_1}{n_2}\) ways to choose the second group from the remaining objects. Continuing like this until all the groups are selected, by the multiplication principle there are \[\begin{aligned} \binom{n}{n_1} \times \binom{n - n_1}{n_2} \times \binom{n - n_1 - n_2}{n_3} \times \dots \times \binom{n_{k-1} + n_k}{n_{k-1}} \times \binom{n_k}{n_k} \end{aligned}\] ways to choose all the groups. Writing each binomial coefficient in terms of factorials, and doing (lots of nice) cancelling, we end up with our expression for the multinomial coefficient.

As it turns out, the multinomial coefficient \(\binom{n}{n_1, n_2, \ldots, n_k}\) is also the number of different (i.e. distinguishable) permutations of \(n\) objects of which \(n_1\) are identical and of type 1, \(n_2\) are identical and of type 2, …, \(n_k\) are identical and of type \(k\) (where \(n = n_1 + n_2 + \dots + n_k\)).

Suggested exercises: Q11 – Q17.

1.3 Conditional Probability and Bayes’ Theorem

Sometimes, knowing whether or not one event has occurred can change the probability of another event. For example, if we know that the score on a die was even, there is a one in three chance that we rolled a two (rather than one in six). Gaining the knowledge that our score is even affects how likely it is that we got each possible score.

Writing conditional probabilities in this way allows us to “invert” them; quite often, one of \(\mathbb{P}(A \mid B)\) and \(\mathbb{P}(B \mid A)\) is easier to spot than the other.

1.4 Independence

When events \(A\) and \(B\) are independent, we have \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{P}(A \cap B) = \mathbb{P}(A) \mathbb{P}(B). \end{aligned}\]

1.5 Partitions

Suppose we can separate our sample space into \(n\) mutually disjoint events \(E_1, E_2, \dots, E_n\): we know that exactly one of these events must happen. We call the collection \(\{ E_1, E_2, \dots, E_n\}\) a partition, and we can use it to break down the probabilities of different events \(A \subseteq S\).

First, we can write \[\begin{aligned} A = (A \cap E_1) \cup (A \cap E_2) \cup \dots \cup (A \cap E_n), \end{aligned}\] so that \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{P}(A) = \mathbb{P}(A \cap E_1) + \mathbb{P}(A \cap E_2) + \dots + \mathbb{P}(A \cap E_n). \end{aligned}\] We can also introduce conditional probability, to get the partition theorem: \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{P}(A) = \mathbb{P}(A \mid E_1)\ \mathbb{P}(E_1) + \mathbb{P}(A \mid E_2)\ \mathbb{P}(E_2) + \dots + \mathbb{P}(A \mid E_n)\ \mathbb{P}(E_n). \end{aligned}\] The partition theorem is useful whenever we can break an event down into cases, each of which is straightforward.

Suggested exercises: Q18 – Q26.

1.6 Random variables

We won’t ever need to worry about the “well-defined” part of the definition in this module, but, strictly speaking, there do exist complicated real-valued functions on certain sample spaces which are not random variables.

1.6.1 Discrete random variables

To describe a discrete random variable \(X : S \to \mathbb{R}\), we can use its probability distribution, which is sometimes called a probability mass function.

Recall here that the event \(\{X = x\}\) is given by \(\{X = x\} = \{s \in S \mid X(s) = x\} \subseteq S\). In a probability distribution, the probabilities must be non-negative and must sum to 1. To find the probability that \(X\) takes values in an interval \([a,b]\), we have \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{P}(a \leq X \leq b) = \sum_{a \leq x_i \leq b} \mathbb{P}(X = x_i). \end{aligned}\]

1.6.1.1 Joint and marginal distributions

Recall here that the event \(\{X = x, Y=y\}\) is given by \(\{X = x, Y=y\} = \{X=x\} \cap \{ Y= y\} \subseteq S\). Moreover, as in the case of the probability distribution of a single random variable, the probabilities in a joint probability distribution must be non-negative and must sum to 1.

We can find the marginal probability distributions of \(X\) and \(Y\) from the joint distribution, by summing across the rows or columns: \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{P}(X=x_k) =\sum_{j} \mathbb{P}(X=x_k,Y=y_j), \\ \mathbb{P}(Y=y_j) =\sum_{k} \mathbb{P}(X=x_k,Y=y_j). \end{aligned}\]

Two discrete random variables \(X\) and \(Y\) are said to be independent if \[\mathbb{P}(X = x_k, Y = y_j) = \mathbb{P}(X = x_k) \, \mathbb{P}(Y = y_j)\] for all possible pairs \((x_k, y_j)\) of values of \(X\) and \(Y\).

1.6.2 Continuous random variables

When our random variable is continuous, we cannot describe its probability distribution using a list of probabilities. Instead, we use a probability density function (pdf), \(f_X(x)\).

To find the probability that \(X\) lies in an interval \([a,b]\), we have \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{P}(a \leq X \leq b) = \int_a^b f_X(x) \, dx. \end{aligned}\]

Remember that the density \(f_X(x)\) is not the same thing as \(\mathbb{P}(X=x)\). In fact, for every \(x\), we have \(\mathbb{P}(X=x) = 0\).

Another way of specifying the distribution of a continuous random variable is through its cumulative distribution function (cdf) \(F_X : \mathbb{R} \to [0,1]\), given by \[\begin{aligned} F_X(x) = \mathbb{P}(X \leq x) = \int_{-\infty}^x f_X(t) \, dt. \end{aligned}\]

1.6.2.1 Joint and marginal distributions

As it is a density, the function \(f_{X,Y}\) is non-negative and must integrate to 1. The probability that \(X\) and \(Y\) take values in a region \(A\) of the \(xy\)-plane is given by the double integral (to be discussed in Chapter 6 \[ \mathbb{P}( (X,Y) \in A) = \iint_A f_{X,Y}(x,y) \, dx dy. \tag{1.1}\]

We can find the marginal probability distributions of \(X\) and \(Y\) from the joint distribution, by integrating out one of the variables: \[\begin{aligned} f_X(x) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty f_{X,Y}(x,y) \, dy \\ f_Y(y) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty f_{X,Y}(x,y) \, dx. \end{aligned}\]

Suggested exercises: Q27 – Q32.

1.7 Expectation and Variance

While the probability distribution or probability density function tells us everything about the distribution of a random variable, this can often be too much information. Quantities which instead summarise the distribution can be useful to convey information about our random variable without trying to describe it in its entirity.

Summaries of a distribution include the expectation, the variance, the skewness and the kurtosis. In this course, we’re only interested in the expectation, which tells us about the location of the distribution, and the variance, which tells us about its spread. The skewness tells us about the symmetry of the distribution about its expectation, while the kurtosis tells us about the likelihood of the random variable taking values far away from the mean.

1.7.1 Expectation

1.7.1.1 Properties of Expectation

Linearity: If \(X\) is a random variable and \(a\) and \(b\) are (real) constants, then \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[aX + b] = a \, \mathbb{E}[X] + b. \end{aligned}\]

Additivity: If \(X_1, X_2, \dots, X_n\) are random variables, then \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[X_1 + X_2 + \dots + X_n] = \mathbb{E}[X_1] + \mathbb{E}[X_2] + \dots + \mathbb{E}[X_n]. \end{aligned}\]

Positivity: If \(X\) is a positive random variable (that is, if \(\mathbb{P}(X \geq 0) = 1\)), then \(\mathbb{E}[X] \geq 0\).

Independence: If \(X\) and \(Y\) are independent random variables, then \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[XY] = \mathbb{E}[X] \, \mathbb{E}[Y]. \end{aligned}\]

Expectation of a function: If \(X\) is a random variable and \(r\) is a (nice1) function, then \(r(X) = r \circ X\) is a random variable with expectation \[\mathbb{E}[r(X)] = \begin{cases} \sum_{x} r(x)\, \mathbb{P}(X=x) \,, & \text{if $X$ is discrete,} \\[3mm] \int_{-\infty}^\infty r(x) f_X(x) \, dx \,, & \text{if $X$ is continuous.} \end{cases}\]

1.7.2 Variance

By expanding out the brackets and using the linearity of the expectation, we can rewrite the variance as \[\begin{aligned} \text{Var}(X) = \mathbb{E}[X^2] - \mathbb{E}[X]^2. \end{aligned}\]

The variance is always positive, because it is the expectation of a positive random variable. The standard deviation is the square root of the variance: \[\begin{aligned} \sigma_X = \sqrt{\text{Var}(X)}. \end{aligned}\]

1.7.2.1 Properties of Variance

Affine transformations: If \(X\) is a random variable and \(a\) and \(b\) are (real) constants, then \[\begin{aligned} \text{Var}(aX + b) = a^2 \text{Var}(X). \end{aligned}\]

Independence: If \(X\) and \(Y\) are independent random variables, then \[\begin{aligned} \text{Var}(X + Y) = \text{Var}(X) + \text{Var}(Y). \end{aligned}\]

Suggested exercises: Revisit Q30; Q33 – Q37.

1.8 The Binomial Distribution

The expectation and variance of \(X \sim \text{Bern}(p)\) are: \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[X] & = p \\ \text{Var}(X) & = p(1-p). \end{aligned}\]

Suppose we have \(n\) Bernoulli-style trials, which succeed or fail independently of each other, and such that all trials have the same probability \(p\) of succeeding. We count the total number of successes across all the trials.

If \(0 \leq k \leq n\), we have \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{P}(Y = k) = \binom{n}{k} p^k (1-p)^{n-k}. \end{aligned}\] This is because each configuration of \(k\) successes and \(n-k\) successes has probability \(p^k (1-p)^{n-k}\), by the multiplication principle; and there are \(\binom{n}{k}\) different ways of arranging the \(k\) successes and \(n-k\) failures among the trials.

The expectation and variance of \(Y \sim \text{Bin}(n,p)\) are: \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[Y] &= np \\ \text{Var}(Y) &= np(1-p). \end{aligned}\]

1.9 The Poisson Distribution

While the binomial distribution is about counting successes in a fixed number of trials, the Poisson distribution lets us count how many times something happens without a fixed upper limit. This is useful in a lot of real-world contexts, for example:

the number of people who visit a website

the number of yeast cells in a sample (such as in experiments by Gossett at Guinness in the 1920s)

the number of particles emitted from a radioactive sample.

The expectation and variance of \(X\) are \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[X] = \text{Var}(X) = \lambda. \end{aligned}\]

1.9.1 Using the Poisson distribution to approximate the binomial distribution

Instead of thinking about our time period \([0,s]\) as one long interval, we can split it up into \(n\) smaller ones (each one will have length \(\frac{s}{n}\)).

Suppose we count the number of sub-intervals in which events occur. If the sub-intervals are small enough, it is very unlikely that there will be multiple events in any of them, and the probability that there is one event will be \(p \approx \frac{rs}{n} = \frac{\lambda}{n}\).

We can view the sub-intervals as \(n\) independent trials, and the total number of successes becomes binomially distributed.

This is a good approximation because the probabilities \(\mathbb{P}(X=k)\) in the binomial distribution \(\text{Bin}(n, \frac{\lambda}{n})\) and the Poisson distribution \(\text{Po}(\lambda)\) are similar as long as \(n\) is big enough. That is, for large \(n\) we have \[\begin{aligned} \binom{n}{k} \left( \frac{\lambda}{n}\right)^k \left( 1 - \frac{\lambda}{n} \right)^{n-k} & = \frac{ n(n-1) \dots (n-k+1)}{k!} \frac{\lambda^k}{n^k} \left( 1 - \frac{\lambda}{n} \right)^{n-k} \\ & = \frac{ n(n-1) \dots (n-k+1)}{n^k} \times \left( 1 - \frac{\lambda}{n} \right)^{n-k} \times \frac{\lambda^k}{k!} \\ & \approx 1 \times e^{-\lambda} \times \frac{\lambda^k}{k!}, \end{aligned}\]

This approximation is good if \(n \geq 20\) and \(p \leq 0.05\), and excellent if \(n \geq 100\) and \(np \leq 10\).

Suggested exercises: Revisit Q38–Q41.

1.10 The Normal Distribution

Unlike the binomial and Poisson distributions, the normal (or Gaussian) distribution is continuous. It is one of the most used (and most useful) distributions. A random variable whose “large-scale” randomness comes from many small-scale contributions is usually normally distributed: for example, people’s heights are determined by many different genetic and environmental factors. All of these different factors have tiny impacts on your final height; overall, the distribution of the height of a random person is roughly normal.

1.10.1 The standard normal distribution

The first version of the normal distribution we will meet is the standard normal.

Properties of the standard normal distribution

The probability density function \(f_Z\) of a random variable with standard normal distribution is symmetric about 0. Then \[\mathbb{P}(Z \leq z) = \mathbb{P}(Z \geq - z) = \mathbb{P}(-Z \leq z),\] which implies, in particular, that the random variable \(-Z\) has the same (normal) distribution as \(Z\).

This symmetry also means that \(x f_Z(x)\) is an odd function; so the expectation of \(Z\) is zero.

The variance of \(Z\) is \[\begin{aligned} \text{Var}(Z) & = \mathbb{E}[Z^2] - 0 \\ & = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} x^2 f_Z(x) \, dx \\ & = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{\infty}^{\infty} x^2 e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}} \, dx = 1. \end{aligned}\] (You can find this via integration by parts.)

The cumulative distribution function for \(Z\)

There is no neat (“algebraic”) expression for \(\Phi(z)\): in practice, when we need to evaluate it we use numerical methods to get (usually very good) approximations. These values are traditionally recorded in tables but usually, they’re built into computer software and some calculators.

Some useful properties of \(\Phi(z)\), which reduce the number of values we need in the tables, are:

Because \(f_Z(x)\) is symmetric, we have \[\Phi(z) = \mathbb{P}(Z \leq z) = \mathbb{P}(Z \geq - z) = 1 - \Phi(-z) \,.\]

We have \(\Phi(0) = \frac{1}{2}\).

\(\mathbb{P}(a \leq Z \leq b) = \Phi(b) - \Phi(a)\).

Interpolation: When the value we need to find isn’t in a table we have access to, we can interpolate. If \(a < b < c\) and we know \(\Phi(a)\) and \(\Phi(b)\), we approximate: \[\begin{aligned} \Phi(b) \approx \Phi(a) + \frac{b-a}{c-a} \left(\Phi(c) - \Phi(a) \right). \end{aligned}\]

For example, most normal tables only go to two decimal places, but \(\Phi(0.553)\) will be approximately \((0.553 - 0.55)/(0.56-0.55) = 0.3\) of the way between \(\Phi(0.55)\) and \(\Phi(0.56)\).

1.10.2 General normal distributions

We can also write this in the other direction: \(X \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu, \sigma^2)\) if \(X = \sigma Z + \mu\). Since the distribution of \(Z\) is symmetric, we use the convention \(\sigma > 0\).

Properties of general normal distributions

The expectation of \(X\) is \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[X] &= \mathbb{E}[\sigma Z + \mu] \\ &= \mu + \sigma \, \mathbb{E}[Z] \\& = \mu + 0 = \mu. \end{aligned}\]

The variance of \(X\) is \[\begin{aligned} \text{Var}(X) & = \text{Var}(\sigma Z + \mu) \\ & = \sigma^2 \, \text{Var}(Z) \\ & = \sigma^2. \end{aligned}\]

The probability density function of \(X\) is \[\begin{aligned} f_X(x) = \frac{1}{\sigma} f_Z\left(\frac{x-\mu}{\sigma} \right) = \frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{ 2 \pi}} \exp \left\{ -\frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{x-\mu}{\sigma} \right)^2 \right\}. \end{aligned}\]

The cumulative distribution function of \(X\) is given by \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{P}(X \leq x) & = \mathbb{P} \left( \sigma Z + \mu \leq \frac{x-\mu}{\sigma} \right) \\ & = \mathbb{P}\left(Z \leq \frac{x-\mu}{\sigma}\right) \\ & = \Phi\left( \frac{x-\mu}{\sigma} \right). \end{aligned}\] We can use the table for the standard normal distribution to evaluate the cumulative distribution function of any normal distribution, by using this transformation.

1.10.3 Using the normal distribution to approximate the binomial and Poisson distributions

Just as we can use the Poisson distribution to approximate specific probabilities in the binomial distribution, we can use the normal distribution to approximate cumulative probabilities. If \(n\) is large and \(X \sim \text{Bin}(n,p)\), then approximately we have \(X \sim \mathcal{N}(np, np(1-p))\).

In particular, \[\mathbb{P}(X \leq k) \approx \Phi\left( \frac{ k-np}{\sqrt{np(1-p)}} \right).\]

This is a useful approximation when both \(np\) and \(np(1-p)\) are at least 10; as the two values increase, the approximation gets better.

Similarly, we can use the normal distribution to approximate the cumulative probabilities in the Poisson distribution: if \(X \sim \text{Po}(\lambda)\), then approximately we have \(X \sim \mathcal{N}(\lambda, \lambda)\) and \[\mathbb{P}(X \leq k) \approx \Phi \left( \frac{k-\lambda}{\sqrt{\lambda}} \right).\]

This is a useful approximation when \(\lambda\) is at least 5, and gets better as \(\lambda\) increases.

Suggested exercises: Q42 – Q45.

1.11 The Central Limit Theorem

1.11.1 Experimental errors

Assumption: We will assume that there are no systematic errors or bias in the experiment; in other words, \(\mathbb{E}[\varepsilon] = 0\).

If the variance of \(\varepsilon\) is \(\text{Var}(\varepsilon) = \sigma^2\), then \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[X] &= \mu + \mathbb{E}[\varepsilon] = \mu + 0 = \mu \\ \text{Var}(X) &= 0 + \text{Var}(\varepsilon) = \sigma^2. \end{aligned}\] This means that, on average, the value of our measurement is a good estimate of the value of \(\mu\); however,if the variance of \(\varepsilon\) is large, our measurement will have quite a high probability of being far from the true value.

To improve our estimate, we can do one of two things:

try to improve our measurement technique, to reduce the variance

take more measurements!

1.11.2 The sample mean

Before we take our measurements, this is also a random variable; afterwards, it is just a number. To distinguish between the two situations, we use \(\overline{X}\) for the random variable, and \(\overline{x}\) for the number.

It is perhaps worth remarking that the definition of the sample mean is a little ambiguous, as \(\overline X\) is not defined on the same sample space as \(X_1, X_2, \dots, X_n\). Indeed, if \(S\) is the sample space on which each \(X_j\) is defined (i.e. \(X_j : S \to \mathbb{R}\)), then the sample mean is defined on the \(n\)-fold product sample space \(S \times S \times \dots \times S\) via \(\overline X(s_1, s_2, \dots, s_n) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{j=1}^n X_j(s_j)\). That is, we take the list \((s_1, s_2, \dots, s_n) \in S \times S \times \dots \times S\) of \(n\) outcomes (e.g. of an experiment repeated \(n\) times), then evaluate the \(j^\text{th}\) random variable \(X_j\) on the \(j^\text{th}\) outcome \(s_j\) and, finally, compute the average of the values obtained. Let’s look at an example.

Assumption: We assume that \(X_1, X_2, \dots, X_n\) are i.i.d. with shared mean \(\mu\) and variance \(\sigma^2\). Then \[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}[\overline{X}] & = \frac1n \sum_{j=1}^n \mathbb{E}[X_j] = \frac{n}{n} \mu = \mu \\ \text{Var}(\overline{X}) & = \frac1{n^2} \sum_{j=1}^n \text{Var}(X_j) = \frac{n}{n^2} \sigma^2 = \frac{\sigma^2}{n}. \end{aligned}\]

So the expectation of the sample mean is always \(\mu\): we call it an unbiased estimator for the mean. On the other hand, the variance is always smaller than \(\sigma^2\) , and decreases as we increase \(n\). By taking a large enough sample size, we can get as small a variance as we want.

If \(n\) is large enough, the sample mean will give an accurate estimate for the true mean \(\mu\). This result is called the Law of Large Numbers, which says that \(\overline{X}\) converges2 to \(\mu\) as \(n \to \infty\).

1.11.3 The Central Limit Theorem

We know that the sample mean will be quite close to the true value \(\mu\) on average. The Central Limit Theorem tells us more about the distribution of the error.

Here, when we say that the distribution is approximately normal, we mean that \[\mathbb{P}(a \leq \overline{X} \leq b ) \approx \Phi \left( \frac{b-\mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}} \right) - \Phi \left( \frac{a-\mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}} \right),\] whatever the values of \(a\) and \(b\).

Suggested exercises: Q46–Q50.