$$ \newcommand{\pr}[1]{\mathbb{P}\left(#1\right)} \newcommand{\cpr}[2]{\mathbb{P}\left(#1\mid\,#2\right)} \newcommand{\expec}[1]{\mathbb{E}\left[#1\right]} \newcommand{\var}[1]{\text{Var}\left(#1\right)} \newcommand{\sd}[1]{\sigma\left(#1\right)} \newcommand{\cov}[1]{\text{Cov}\left(#1\right)} \newcommand{\cexpec}[2]{\mathbb{E}\left[#1 \vert#2 \right]} $$

9 Limit theorems

9.1 The weak law of large numbers

The results of this section describe limiting properties of distributions of sums of random variables using only some assumptions about means and variances.

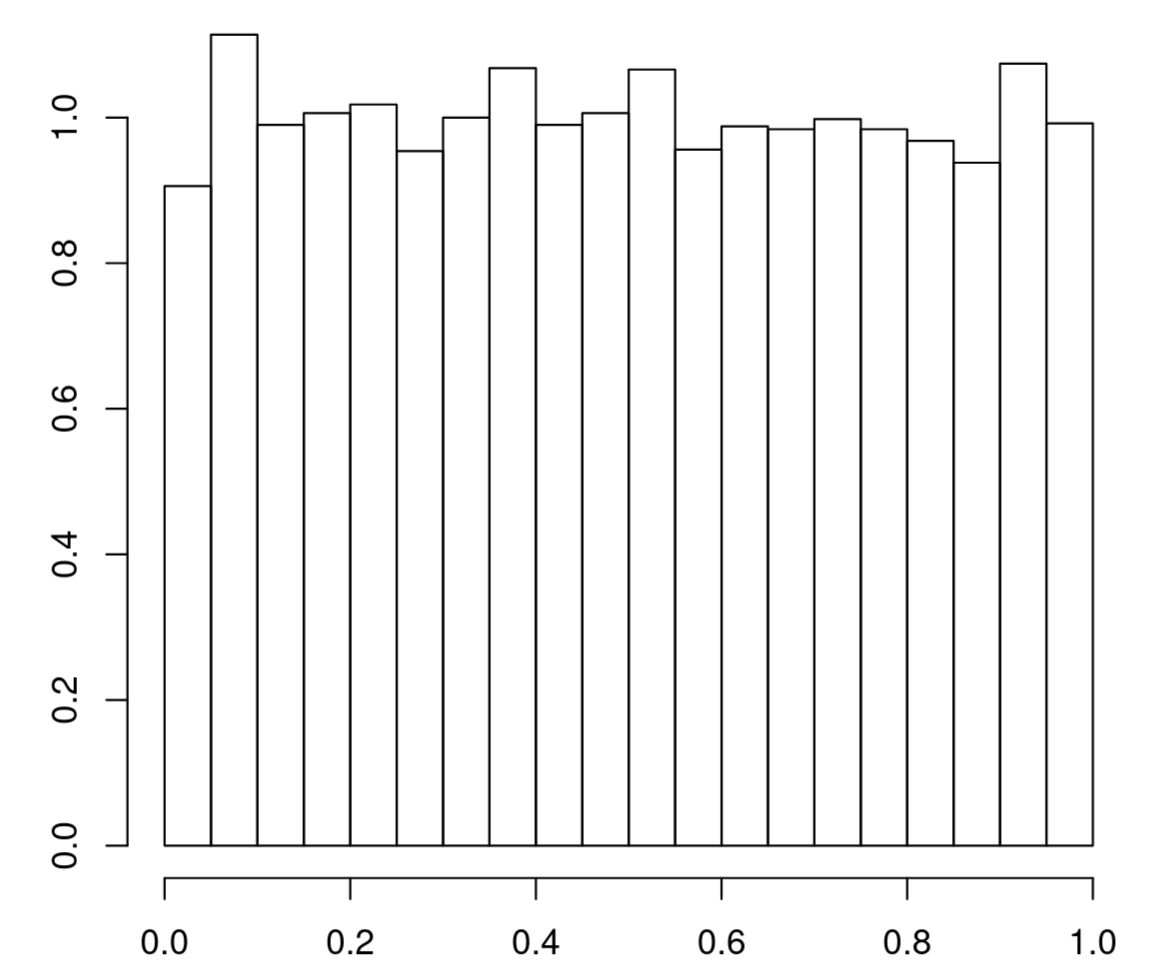

Toss a coin \(n\) times, where the probability of heads is \(p\), independently on each toss. Let \(X\) be the number of heads and let \(B_n:= X/n\) be the proportion of heads in the \(n\) tosses. Then, because \(X\sim\text{Binom}(n,p)\) has expectation \(np\) and variance \(np(1-p)\), \[\begin{aligned} \expec{B_n} &= \expec{X}/n = p, & \var{B_n} &= \var{X}/n^2 = p(1-p)/n. \end{aligned}\]

So, by Chebyshev’s inequality, for any \(\epsilon>0\), \[\pr{|B_n - p| \geq \epsilon} \leq \frac{p(1-p)}{n\epsilon^2}.\] Whence, \[\pr{|B_n - p| \geq \epsilon}\to 0 \text{ as } n \to \infty,\] no matter how small \(\epsilon\) is. In other words, as \(n \rightarrow \infty\), the sample proportion is with very high probability within any tiny interval centred on \(p\).

The same argument applies more generally.

In other words, the sample average has a very high probability of being very near the expected value \(\mu\) when \(n\) is large. The type of convergence in Equation 9.1 is called convergence in probability: the weak law of large numbers says that “\(\bar{X}_n\) converges in probability to \(\mu\)”.

9.2 The central limit theorem

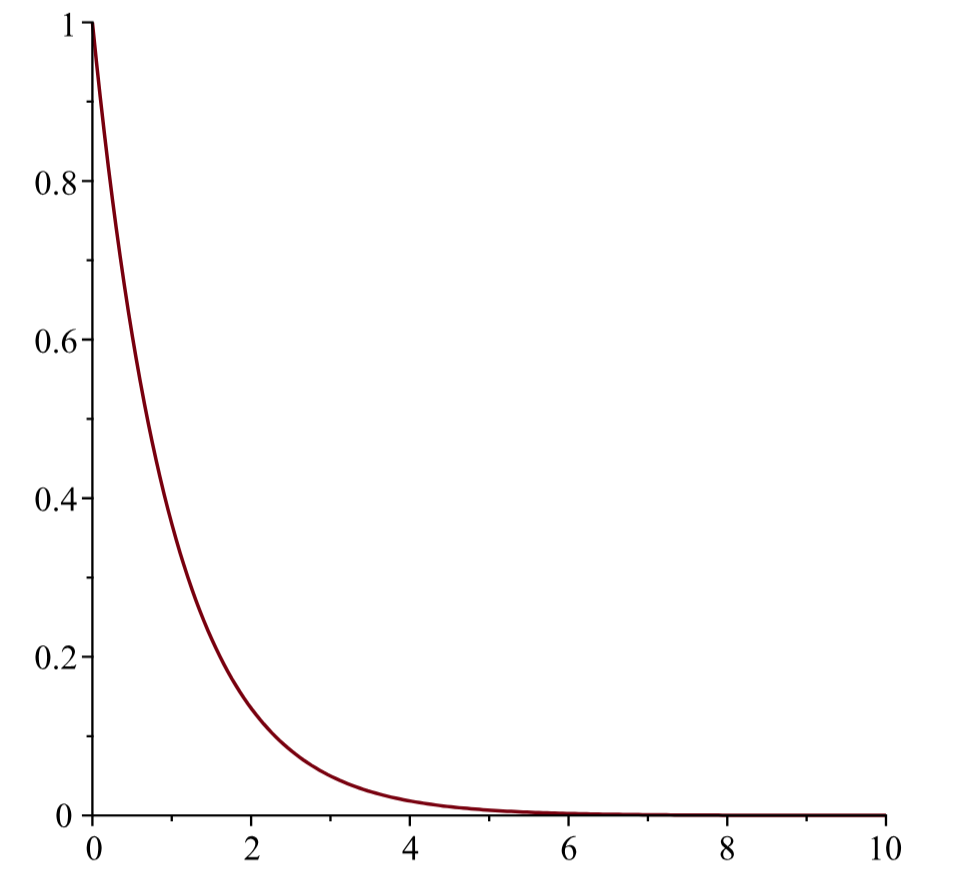

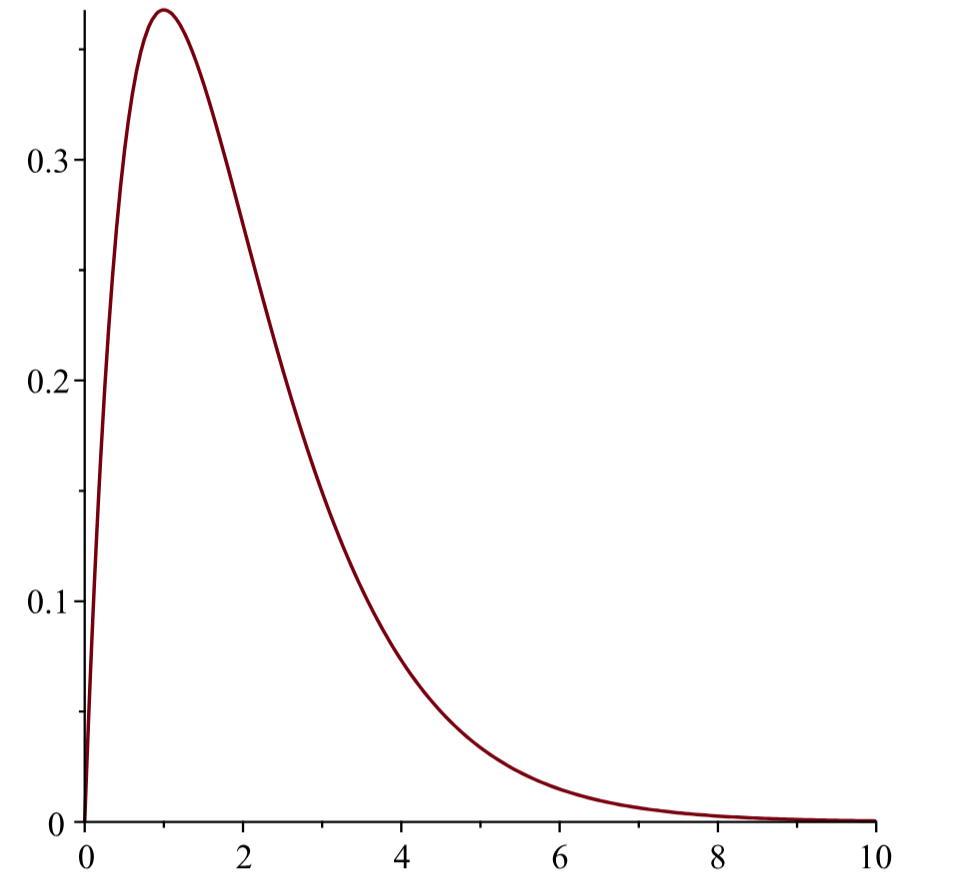

If the law of large numbers is a ‘first order’ result, a ‘second order result’ is the famous central limit theorem, which describes fluctuations around the law of large numbers, and explains, in part, why the normal distribution has a central role in statistics. A sequence of random variables \(X_1, X_2, \ldots\) are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d. for short) if they are mutually independent and all have the same (marginal) distribution.

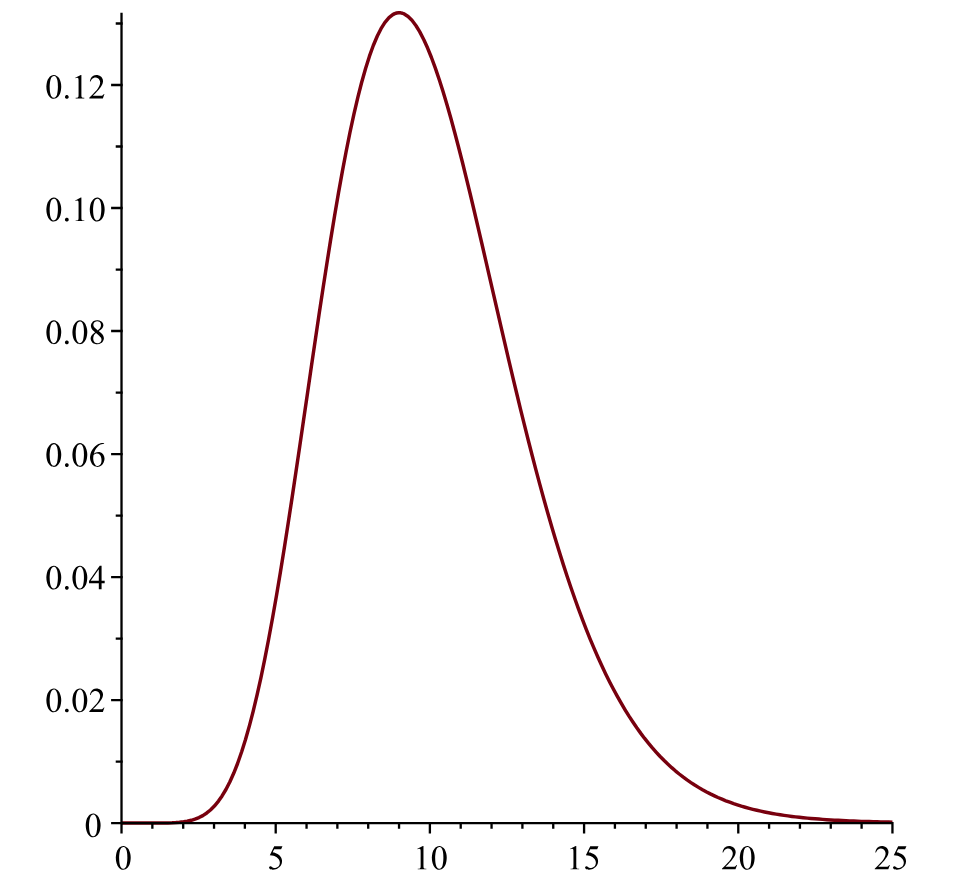

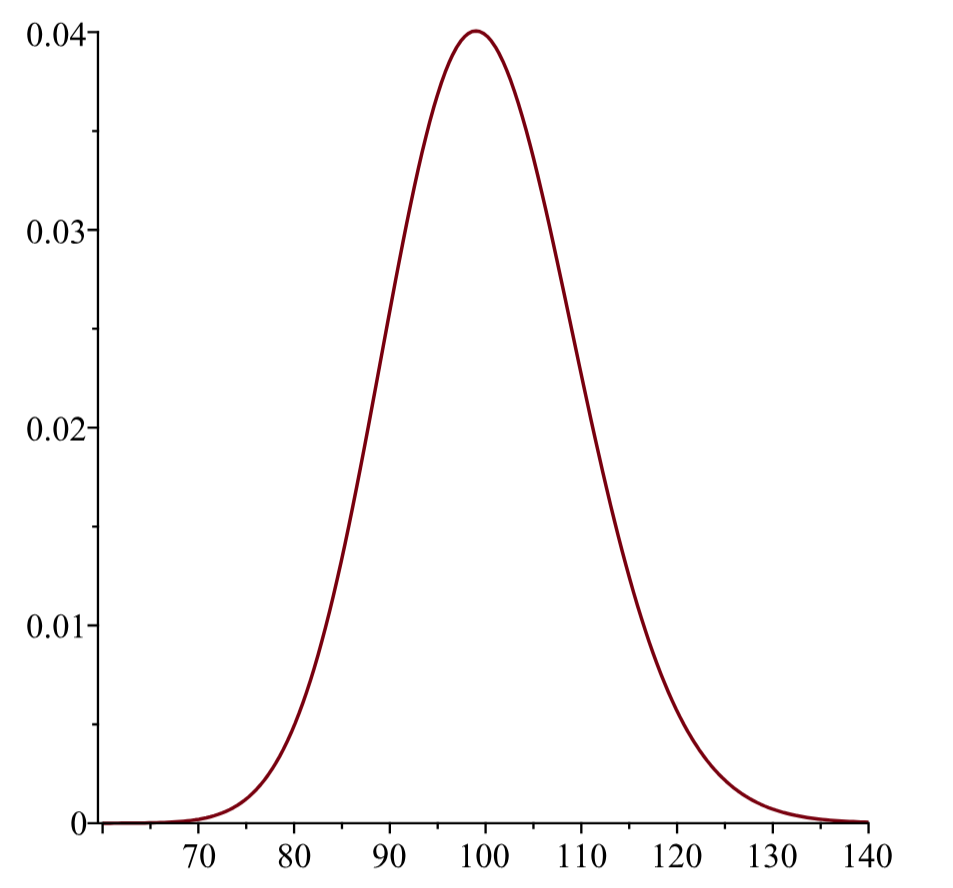

In other words, for large \(n\), we have that approximately \(Z_n \approx \mathcal{N}(0,1)\). Note that the definition of \(Z_n\) is such that \(\expec{Z_n} =0\) and \(\var{Z_n}=1\). The content of the central limit theorem is that it should be approximately normal. Consequently, if we also invoke , we approximately have that \(S_n \approx \mathcal{N}(n\mu,n\sigma^2)\) and \(\bar{X}_n \approx \mathcal{N}(\mu, \sigma^2/n)\), i.e., typical values of \(S_n\) are of order \(\sigma\sqrt{n}\) from \(n\mu\) while typical values of \(\bar{X}_n\) are of order \(\sigma/\sqrt{n}\) from \(\mu\). In other words, for large enough \(n\), by , \[\begin{aligned} \pr{S_n \leq x} &\approx \Phi\left(\frac{x-n\mu}{\sigma\sqrt{n}}\right), \\ \pr{\bar{X}_n \leq x} &\approx \Phi\left(\frac{x-\mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}}\right). \end{aligned}\]

Remember that we can write any binomially distributed random variable as a sum of independent Bernoulli random variables. Consequently:

This means that, when \(X\sim\text{Bin}(n,p)\) with \(0<p<1\) and large enough \(n\), then for any \(x\in\mathbb{R}\), we approximately have that \[\pr{X \leq x} \approx\Phi\left( \frac{x-np}{\sqrt{np(1-p)}} \right)\] For moderate \(n\), a continuity correction improves the approximation; e.g. for \(k\in\mathbb{N}\): \[\begin{aligned} \pr{X \leq k}&=\pr{X\leq k+0.5} \approx \Phi\left( \frac{k+0.5-\mu}{\sigma} \right) \\ \pr{k\le X}&=\pr{k-0.5\le X} \approx 1-\Phi\left( \frac{k-0.5-\mu}{\sigma} \right) \end{aligned}\]

The proof of the central limit theorem requires an important new tool: the moment generating function.

9.3 Moment generating functions

Because \(e^{tX}\ge 0\), we have that \(M_X(t)\ge 0\) by monotonicity of expectations.

Using the Law of the Unconscious Statistician, we can derive the following expressions for \(M_X(t)\): \[\begin{aligned} M_X(t) &= \sum_{x\in \mathcal{X}} e^{tx}p(x) &&\text{if $X$ is discrete, and} \\ M_X(t) &= \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{tx}f(x) \mathrm{d} x &&\text{if $X$ is continuously distributed.} \end{aligned}\] The above sum and integral always exist, but can be \(+\infty\).

The moment generating function has several useful properties. The property that gives the name is revealed by considering the Taylor series for \(e^{tX}\): formally, \[\begin{aligned} M_X(t) & = \expec{ e^{tX} } = \expec{ 1 + t X + \frac{t^2X^2}{2!} + \frac{t^3X^3}{3!} + \cdots } \\ & = 1 + t \expec{ X} + \frac{t^2}{2!} \expec {X^2} + \frac{t^3}{3!} \expec {X^3} + \cdots , \end{aligned}\] at least if \(t \approx 0\). (Some work is needed to justify this last step, which we omit.) This gives the first of our properties.

9.4 Historical context

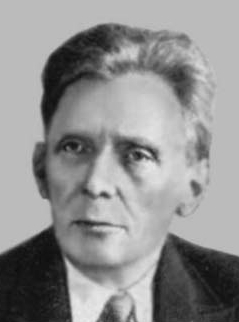

The law of large numbers and the central limit theorem have long and interesting histories. The weak law of large numbers for binomial (i.e. sums of Bernoulli) variables was first established by Jacob Bernoulli (1654–1705) and published in 1713 (Bernoulli 1713). The name ‘law of large numbers’ was given by Poisson. The modern version is due to Aleksandr Khinchin (1894–1959), and our Central Limit Theorem is only a special case—the assumption on variances is unnecessary.

It was apparent to mathematicians in the mid 1700s that a more refined result than Bernoulli’s law of large numbers could be obtained. A special case of the central limit theorem for binomial (i.e. sums of Bernoulli) variables was first established by de Moivre in 1733, and extended by Laplace; hence the normal approximation to the binomial is sometimes known as the de Moivre–Laplace theorem. The name ‘central limit theorem’ was given by George Pólya (1887–1985) in 1920.

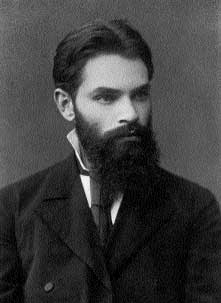

The first modern proof of the central limit theorem was given by Aleksandr Lyapunov (1857–1918) around 1901 (“Lyapunov Theorem,” n.d.). Lyapunov’s assumptions were relaxed by Jarl Waldemar Lindeberg (1876–1932) in 1922 (Lindeberg 1922). Many different versions of the central limit theorem were subsequently proved. The subject of Alan Turing’s (1912–1954) Cambridge University Fellowship Dissertation of 1934 was a version of the central limit theorem similar to Lindeberg’s; Turing was unaware of the latter’s work.